South Eastern Ontario Indigenous History

Indigenous traditional knowledge passed on from one generation to the next would share that the islands and waterways in South Eastern Ontario have been part of Indigenous history since time immemorial. The Haudenosaunee (or Six Nations) traveled these waters in either dug-out or birch bark canoes to harvest fish and wildlife to sustain the long winters. The first documented proof of Indigenous presence would be a stone hunting point found on Gordan Island just east of Gananoque from the Paleo-Indian cultures of 7000 to 9000 years ago.

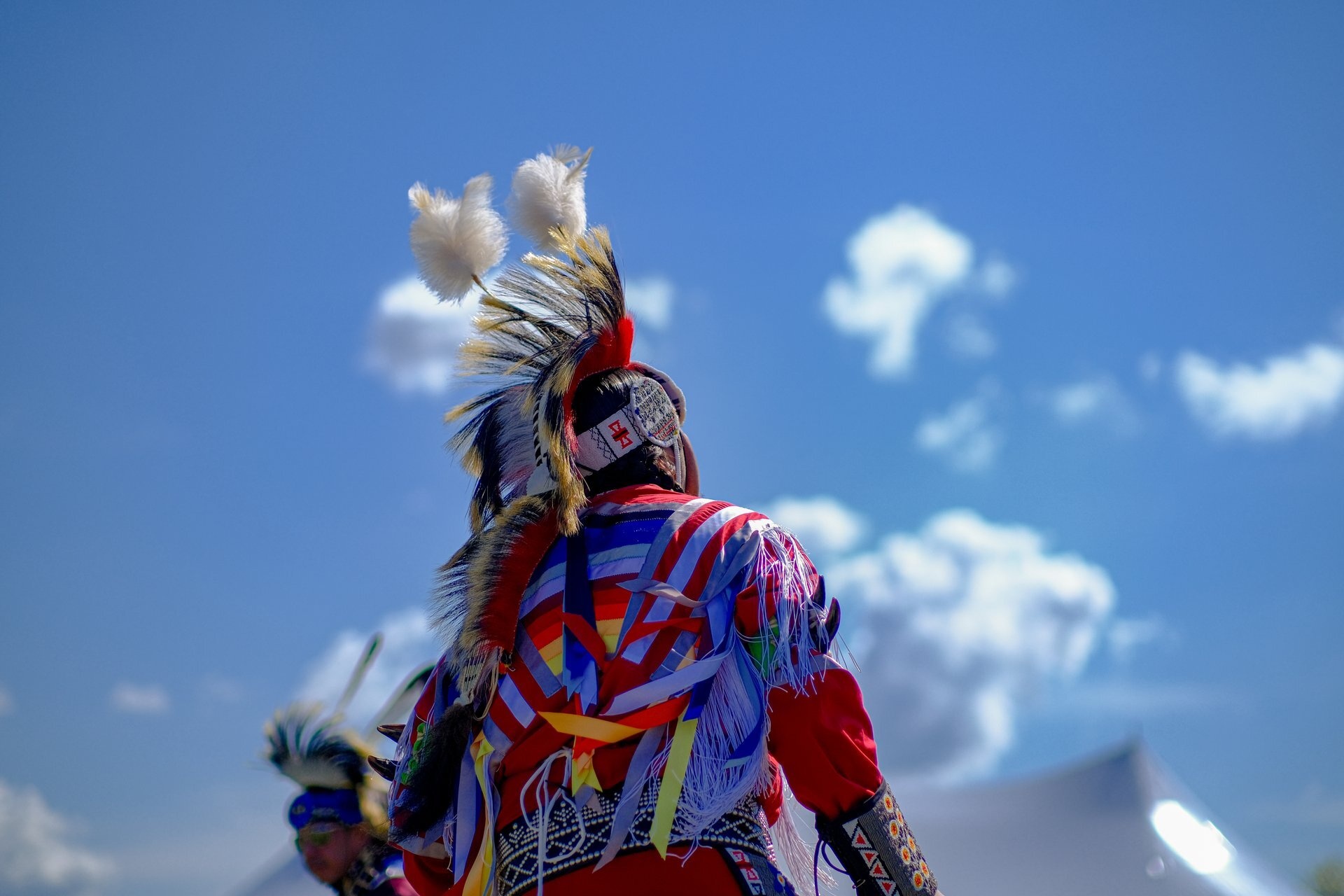

Today, this region provides several authentic ways to experience this Indigenous connection to the land and water. Visitors can feel the spirit of our Indigenous ancestors on the shores of the river or witness the cultural revitalization by visiting a pow-wow. During your time here, you can discover the talent and teachings of our traditional knowledge keepers, support local artisans, and find authentic experiences that connect you to the rich history of this land in making baskets or lacrosse sticks, medicine walks and tasting traditional Indigenous foods.

Brockville

The Thousand Islands were once referred to as the “Garden of the Great Spirit” or Manitouana. Many Indigenous nations, including Algonquin and Haudenosaunee, travelled these same waters to set up camps and enjoy fishing the rich waters of the river for tens of thousands of years. These islands have been part of their traditional lands since time immemorial.

Early French explorers, fur traders and missionaries who were following the St. Lawrence River also shared accounts of stopping at places like Toniata (believed to be Grenadier Island) to visit Indigenous encampments where several hundred had gathered. They recall counts of summer camps with wigwams covered in skins, set up on breezy points of the islands to avoid mosquitoes. These islands provided all they needed – fishing for bass, perch, pike, and suckers with the hunters making their way in the fall to the rivers’ edge to hunt moose, deer and bear along with smaller game like raccoon, turkey, beaver and waterfowl. The Thousand Islands provided a rich and bountiful place for these communities to live for the summer providing fish and meat to smoke for the long winter months.

Eventually, the traditional fishing camps were abandoned after European settlers started moving in around 1784, following the end of the American Revolution. The Indigenous people continued to visit the area to fish but no longer set up camp as it became a popular tourist destination. However, the communities today remain spiritually and culturally connected to the Islands.

Gananoque

Gananoque is a name of Indigenous origin with some saying the name means “Town on two Rivers” (the St Lawrence River and the Gananoque River), or “water flowing over rocks”. Local historian John Nalon writes that to many, the name means “the Place of Health” since First Nations would make their way to these shores where the Gananoque River flows into the St Lawrence every spring. It is said that as they enjoyed the spring sunshine in this place their winter illnesses, including scurvy, were healed.

Our Indigenous oral histories tell us that our communities have visited, camped, and harvested from the bountiful lands of Gananoque for tens of thousands of years. Gananoque has been one of the key locations for the discovery of an ancient artifact to support our oral histories. A stone hunting point was found on Gordon Island, just east of Gananoque, which can be traced to Paleo-Indian cultures that inhabited southern Ontario over 9000 years ago. There are some 40 archeological sites on the islands that support the oral history of our communities’ connection to Gananoque.

Akwesasne

Cornwall Island is home to a unique community that truly reflects the ancient and traditional territorial lands of the Haudenosaunee community. Their settlement spans all shores of the St. Lawrence River within two provinces (Ontario and Quebec) and two countries (Canada and New York, USA). Akwesasne means “the Land where the partridge drums”, referring to the rich and abundant wildlife in the area.

The oral history of our elders tells us that the Mohawks of Akwesasne are the descendants of the original inhabitants who were called the St. Lawrence Valley Iroquoian who settled along these banks thousands of years ago, long before European contact. Located on the grand St. Lawrence River, with the Raquette River and St. Regis River also winding through the territory, makes it easy to understand why the community’s earliest ancestors made their home here. The waterways provided not only transportation and trading routes, but also an abundance of wildlife to fish and hunt. Haudenosaunee lived in longhouses up until the late 1800s. A longhouse is a long and narrow bark-covered house. Panels of elm bark were lashed to wooden poles, usually made from hickory, cedar, or elm. Historically, each village belonged to a clan. All the women and children living in a longhouse belonged to the same clan, and the husbands and fathers would join from a different village and clan as it is a matriarchal society.

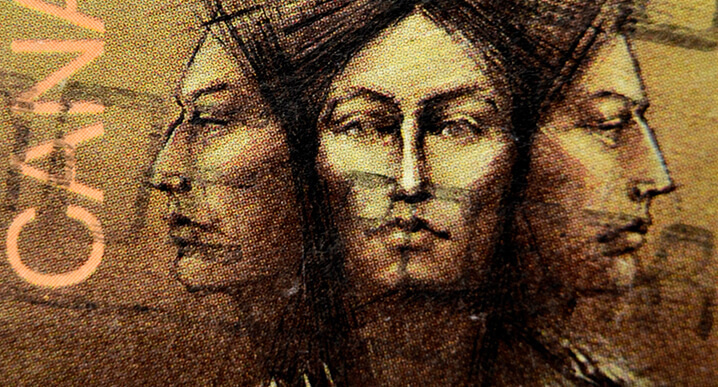

For thousands of years, the Haudenosaunee have been using and trading a special shell bead called wampum. Wampum beads are drilled from specific types of hard clam and large snail shells native to the Eastern coastline creating purple and white beads. The Haudenosaunee have treated wampum beads with very high or sacred regard throughout history, using them in ceremonies and for other important purposes like creating wampum belts which carried special meaning. Two wampum belts are significant to Akwesasne, including the Two Row Wampum belt. This belt has two parallel rows down the center, which is said to symbolize the Haudenosaunee people and European settlers who are travelling the “River of Life” in separate but equal vessels. This symbolizes their culture, laws, traditions, and customs and demonstrates a mutual respect of travelling this life path side by side, not interfering with one another. Some of the ancient wampum belts are on display in the Native North American Traveling College on Cornwall Island.

Today, Akwesasne welcomes visitors to share in the Mohawk Spirit. They provide several unique and enriching experiences that provide an introduction to Akwesasne life, history, art and food.

Tyendinaga Mohawk

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory is the home of “Kenhtè:ke Kanyen’Kehá:ka,” meaning the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, whose ancestors were the Fort Hunter Mohawks. The Mohawks are Rotinonhsyón, or Six Nations Confederacy, which translates in English to “People of the Longhouse.” They are often referred to as the keepers of the Eastern Door.

The Fort Hunter Mohawks and allies were forced to relocate to Lachine, Quebec, during the American Revolution. In 1783, a leader of the Fort Hunter Mohawks, Captain John Deserontyon, “Yodeserōntyon”, meaning, “the lightning has struck”, selected lands on the Bay of Quinte for a new homeland.

They arrived on the shores of the Bay of Quinte on May 22, 1784, with about 20 families and were met by the Mississaugas who lived in the area. The community marks this event with a Landing re-enactment and a Thanksgiving Ceremony for the safe arrival of their ancestors held on the weekend closest to the 22nd of May at 353 Bayshore Rd. After nine years of waiting for a promised grant of land, the Simcoe Deed, also known as Treaty 3½, granted the land "To the Chiefs, Warriors, Women and People of the Six Nations" after the American Revolution. The lands promised, which was known as the Mohawk Tract, was only 12 miles along the Bay of Quinte, and 13 miles deep but in actual fact it was smaller. Oral histories tell us that the Peacemaker, “Tekanawí:ta”, who brought peace to the Confederacy, was born on Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. When visiting, take time to visit the memorial at the Community Centre at 1807 York Road.

Today, Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, continues to welcome visitors to experience their rich history with historical sites, such as the beauty of the Bay of Quinte and numerous shops that carry authentic arts and crafts, restaurants, and events like the Annual Pow Wow, usually held the 2nd weekend in August in the Tsi Tkerhitoton Park at 275 Bayshore Rd., the Annual Mohawk Fair, usually held in September at 1807 York Rd. A National Historic Site is Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal, Christ Church on 52 South Church Lane. This is one of two Royal Chapels in Canada. The other resides on the Six Nations of the Grand River, Oshweken, Ontario.

Kingston

The region the city of Kingston now occupies has been home to Indigenous People since time immemorial. Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and Huron-Wendat people have shared this area. The concept of the sharing of land by multiple peoples is known as “A Dish with one Spoon”. Today, it is home to over 7,000 residents who identify as First Nations, Inuit, or Metis. This area of the north shore of Lake Ontario was known as Katarokwi, which means a place where there is clay or where the limestone is. The Algonquin term Cataracoui means great meeting place and was translated by the French into Cataraqui, a term that is used throughout the Kingston area today.

The history of Indigenous People in this region is complex and pre-dates geo-political boundaries that exist today. Communities of Late Woodland people (approximately 1200 to 1450) and the St. Lawrence Iroquois (16th century) were known to occupy this region. In the late 17th century, Haudenosaunee communities (Seneca, Cayuga and Mohawk) were established at various spots heading east along the shore of Lake Ontario. The Mississaugas (Anishinaabe), established communities in the region in the early 18th century, and ceded the area and surrounding territory to the British Crown by the 1783 Crawford Purchase. After the American Revolution, Kingston became an important centre for the Indigenous people of the area.

Konwatsi’tsiaiénni, “someone lends her a flower”, Molly Brant, a Mohawk woman of distinction, and sister of Captain Joseph Brant (who, with his followers, established the Six Nations of the Grand River) made Kingston her home until her passing in 1796 and was buried at St. Paul’s Church on Queen at Bagot Streets. Mississauga and Mohawk people came regularly for trade and the for payment of annual presents of goods from Crown representatives. The annual presents marked the ongoing relationship with the Crown. Market Square, behind what is now Kingston City Hall, was the main trading location. During the War of 1812 and the Upper Canada Rebellion, Kingston was of central importance to Indigenous warriors and was used as a gathering point and staging centre for military actions.

1000 Islands & Rideau Canal Waterways

Archaeological evidence of Indigenous presence dating back to the Archaic period of 7,000 to 1,000 BC is abundant all along the canal. During this time, Indigenous nations lived along the waterways, as it was their main means of travel. They hunted everything from squirrels to moose and fish and plant food like wild rice and berries found along the shores. As trade for beads of copper, stone, and shell became prominent, these waterways became a major trade route.

Two major and distinct nations inhabited the lands of the Rideau Canal region; the Iroquoian and Algonquin nations. The Algonquin nation occupied most of the Rideau region, although they were nomadic with no permanent settlements. As a hunter-gatherer culture, they used the Rideau River as a source of food, setting up both hunting and fishing camps throughout the region and establishing villages along the shores of the Ottawa River.

By about 1,000 A.D. the Iroquois nation were building large, palisaded villages on the shores throughout the region. These communities were agriculturally based, growing corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco and lived in large longhouses. Shortly before European arrival, the Iroquois formed a treaty of peace forming the five nations, later to become the six nations with the Tuscarora joining in 1722. At the time of European arrival it is estimated that the Indigenous population was almost 60,000 and with the arrival of early Europeans, the lifestyle of all Indigenous peoples in the region changed drastically with exposure to new diseases and introduction to the fur trade of goods leading to alliances between the French and Algonquin nations and the British and Iroquois nations inevitably leading to conflicts and wars ending in 1701 with a treaty of neutrality with the wars between British and French. Since there were never any permanent communities established along the Rideau, as the Indian Reservations were established, this area was no longer a residence of any Indigenous community but still holds a strong piece of history.

Prince Edward County

On a scenic road to Brighton, is a place of historical significance to the Indigenous peoples of this region called Carrying Place. Carrying Place is not just the oldest road in continuous use in Ontario, it was an important portage route for Indigenous nations following their natural food source through the regions and later to trade. The route was called “Carrying Place” by Indigenous Nations, who would use the path to portage and carry their canoes between the Bay of Quinte and Wellers Bay. The portage trail was used as a trade route by Indigenous people for thousands of years as the trail offered easy access to Lake Ontario and a safer way to portage the dangerous waters of what is now Prince Edward County. At one time, when the waterways were the most popular mode of transportation, Carrying Place was expected to have a brighter future than even Toronto.

The most notable history of the Kente Portage Trail was the site of the Gunshot Treaty of 1787, which saw the purchase of land that stretched from the Bay of Quinte to what is not Etobicoke from the Mississauga Nation. This event is marked by a historical marker on the corner of Old Portage Rd and Loyalist Parkway. The “Gunshot Treaty” refers to the distance a person could hear a gunshot from the lake’s edge and is one of the earliest land agreements between representatives of the Crown and Indigenous People that resulted in a large tract of territory being opened for settlement, which later became part of the Williams Treaty of 1923.

Today, this ancient travel route can take you to experience much of the natural beauty that remains in Prince Edward County.

Prescott-Russell

The significant historical presence of First Nations in the United Counties of Prescott and Russell can be attributed to the region's extensive border with the Ottawa River. The rivers provided access inland and travelling routes to game and fish. The shores and fertile lands provided wild rice and berries. The Anishinaabe people, including the Omàmìwininìwag/Omàmiwinini (Algonquin) Nation – Down-River People, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people, including the Kanienkeha:ka (Mohawk) Nation – People of the Flint, converged to trade. In the Algonquin language, the Ottawa River is known as Kitchi Zibi, meaning “Great River”. The original Anishinaabe word "odaawe" means "a place of trade". Based on archaeological evidence, it can be inferred that the Algonquin people inhabited the Ottawa Valley for a minimum of 8,000 years before the arrival of Europeans in North America.

The Algonquins define themselves by their position on the river, the “down-river” people. Algonquin guides led the first Europeans up the river. The route was later used by French fur traders, and coureur des bois, to reach the interior. The history of the Ottawa River watershed and the Algonquin people are closely intertwined. The Algonquins were semi-nomadic, with shelters that could be easily taken apart and moved. Activities went by seasons. From spring to fall, they gathered resources. They set up camp along the river to fish, hunt and socialize. In winter, they retreated to the bush in extended family groups to hunt game such as moose and deer. Trapping, especially beavers, provided both meat and pelt. Fishing was year-round but most productive in the spring and the fall. In the Lower Ottawa River, they used the slash-and-burn method of agriculture for corn, beans, and peas to supplement their supplies.

Trading was essential, and each nation had its sought-after skills and merchandise. Hurons traded corn and cornmeal, wampum and fish nets. The Nipissings and Algonquins exchanged furs and dried fish. The Ojibway and Cree, often coming from far away, provided extra pelts. Trading was a business and was defined by rules and customs. Treaties of peace and military alliances were to be maintained because only friends could trade.

In the 17th century, many of the nations were affected by European diseases, especially smallpox and warfare with the Iroquois. The lands, which are now Prescott and Russell became a war zone. In 1701, a peace treaty returned tranquillity to the First Nations. The contribution of the Algonquins to the growth of the fur trade in Canada cannot be underestimated. They were both teachers and facilitators. Fur traders learned the Algonquin language to help smooth their travel upriver.

The Algonquins have a saying, "If we cease sharing our stories, our knowledge becomes lost.” Stories of mythical figures, as retold time after time by the elders, are more than entertainment. They provide spiritual guidance to the next generation, they connect past, present, and future.